The movement–the mechanism that measures the passage of time and displays the current time–is the heart of any clock. Most clocks have either a mechanical or a battery-operated quartz movement. While most of today’s clocks have battery-operated movements, older antique clocks have mechanical ones.

Compared to electronic movements, mechanical clock movements are less accurate, often with errors of seconds per day, and they’re suffer from sensitivity to position and temperature, requiring regular maintenance and adjustment.

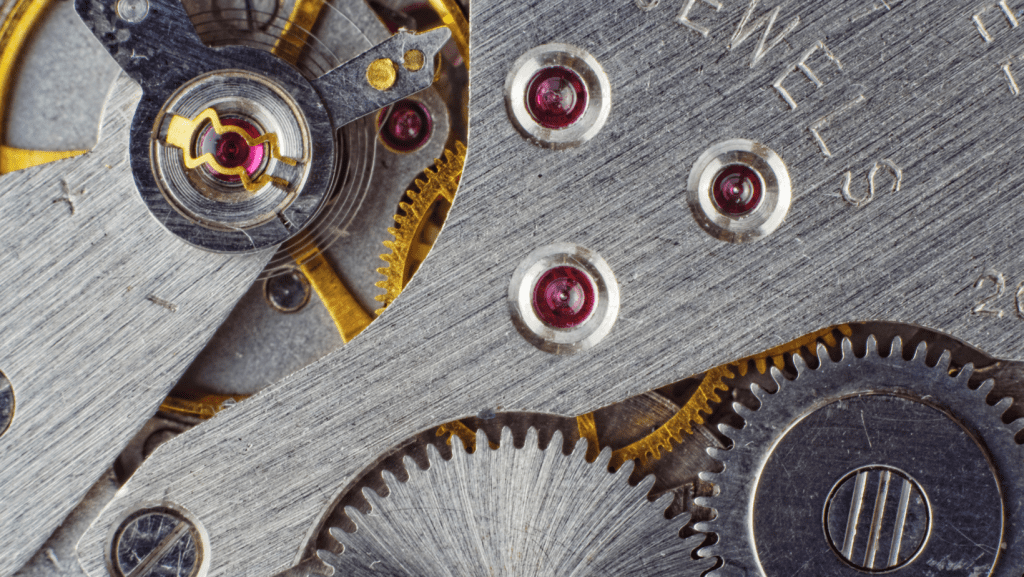

Mechanical clock movements use an escapement mechanism to control and limit the unwinding of the spring, converting what would otherwise be a simple unwinding, into a controlled and periodic energy release. This is accomplished through the use of gears and a lever attached to a pendulum. The most common form in use today is powered by key- wound springs.

The verge escapement, also known as the crown-wheel-and-verge escapement, developed in 1275 C.E., predates the pendulum and works like a teeter- totter. By attaching the verge escapement to a pendulum, clockmakers were able to increase the accuracy of their clocks tremendously, from about 15 minutes per day to 15 seconds per day. Soon clockmakers began retrofitting their clocks with pendulums. But for this to work the axis of the verge had to be horizontal. And though this design was good at keeping time, the pendulum had to swing up to 100 degrees. So to avoid the need for a very large case, clockmakers used a short pendulum.

Clocks from the late 17th century used the anchor escapement, also known as recoil escapement, invented about 1670. Before then, pendulum clocks had used the older verge escapement, which required very wide pendulum swings of about 100 degrees. To avoid the need for a very large case, most clocks using the verge escapement had a short pendulum.

The teeth of an anchor escapement wheel project radially from the edge of the wheel, much like an upside down anchor. This escapement reduced the pendulum’s swing to between four and six degrees, allowing clockmakers to use longer pendulums with slower beats. These required less power to move, caused less friction and wear, and were more accurate than their shorter predecessors. Most longcase clocks use a pendulum about 39 inches long to the center of the bob, with each swing taking one second. This requirement for height, along with the need for a long drop space for the weights that power the clock, gave rise to the tall, narrow case of grandfather clocks, the first made by William Clement about 1680. With the increased accuracy that resulted from these developments, clockmakers began adding minute hands to their clocks around 1690.

When the pendulum swings the lever locks in the tooth of the gear, it produces the tick. The back swing of the pendulum the lever releases the gear produces the tock. The process is repeated over an over until the clock needs winding. Moving the pendulum bob up or down adjusts the speed and accuracy of the clock. Adjusting the bob upward speeds up the clock, adjusting the bob downward slows down the clock.

By 1715, George Graham introduced the dead beat escapement which then led to the development of the extremely accurate lever escapement. Clockmakers rounded the edge of the anchor so as not to lock the gear. This allowed the pendulum to operate the clock on both back and forth swings which greatly reduced wear on the escapement. In most wall clocks that use a pendulum, the pendulum swings once per second. In small cuckoo clocks the pendulum might swing twice a second. In large grandfather clocks, the pendulum swings once every two seconds.

Credited to: http://www.bowerswatchandclockrepair.com/