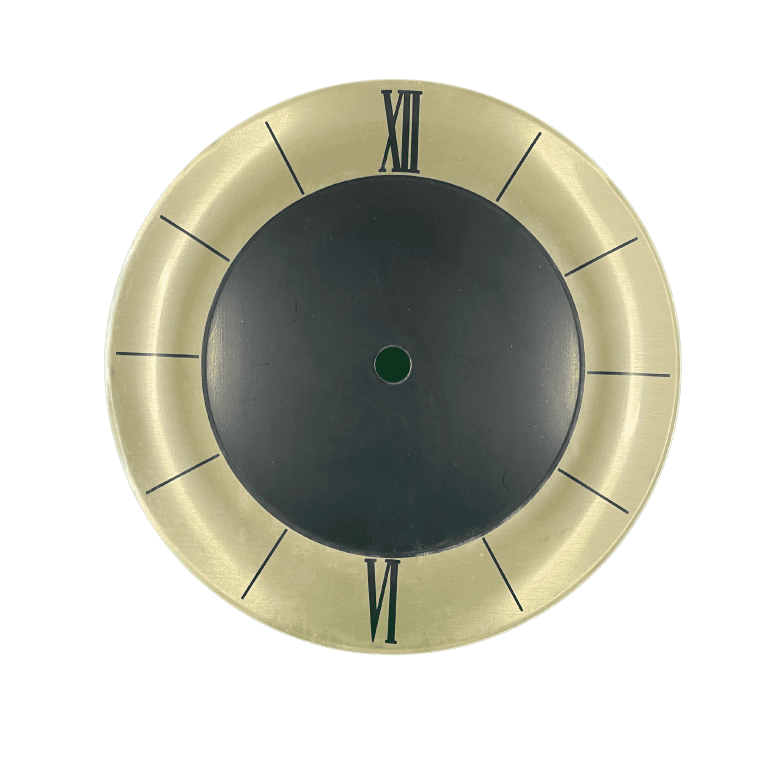

The clock picture at the start of this article is a Kingston Avery we had in last month for service and minor component replacement. Its from about 1730. If you can get one earlier for the same price then do that but 1730 is the start point to work backwards from – maybe even 1740 if the same face design is present.

Kingston Avery made tower clocks as well as grandfathers and were clearly a skilled bunch as you can see from the beautiful quality of the face engraving. Its a good distance from London and its influence but the dial maintains its rigid four spandrel chapter ring layout. Theres engraving on the outer of the face which is a little clumsy but more than forgiveable.

The inner circle is nicely engraved with a soft touch and varying stroke depth on the serifs of the letter which you can imagine was quite a skill. There were no second chances doing that job and so thats why I say that the quality is forgiveable.

Engraving was a really technically hard artisan discipline and the clocks were sold with the mistakes visible. Like diamonds we do not expect flawless quality in everything.

Its also very personal once you own the clock and you regard the errors as a fingerprint rather than a blemish. The correction is often entertaining and tells its own story. When you find some of the errors on the face and realise the gut churning that followed the slip of the engravers tool,you cannot help smiling if not sniggering to yourself. Its worth going to the auction viewings just for that.

For some reason its always the straight lines that overshoot as opposed to any mistakes in the filigree work. Some of them are epic and only a stroke away from “start again” really. A common one is where the engraver just started off in the wrong direction on the cut. Half way down you see him realise its not going to meet up with the V point of the 5 (Roman numeral five [V]), and a new line is started mid-bar!.

Having said this, these engraving errors should not be mistaken for exaggeration of a character stroke which is not that un-common on clocks produced away from the city. A typical example of this might be a long thin bar on an arabic 5 or 4.

The clock pictured has also got the moon dial automata which is a bonus. Dont expect this at the price point you are trying to hit – you will find a price hike in the clocks with moving components on the face other than the hands. Instead you might find a slivered engraved disc with an eagle or similar. This is usually surrounded by two sea serpent spandrels whith cherub corner spandrels. If either of those are different check the back of the clock plate for old spandrel fixing holes that show a change has been made. Clocks were often cannibalised by repairers and makers as spandrels styles changed in line with fashion every few years. Its not a disaster if the spandrels match but you want originals really. I wouldnt buy a clock with replacement spandrel holes. Its just not original enough for me but you dont have to care. It doesn’t matter in any other context than resale value.

Grandfather clock face layout and design evolved over a period of 200 years which give or take was 1660 to 1860. Clocks from about 1730 show this evolution at its most interesting point, and for me, are the best buys as you can get a good price and history a’plenty.

Clocks from between 1700 and 1730 show all the old features of earlier manufacturing face decoration from which things simplified as two handed marking was accepted as the norm.

Having said that from this point onwards, apart from the inner chapter ring marking, nothing was really added in terms of design apart from automata in its various forms (moon dial, rocking ship, etc.). From hereon face design really sort of simplified and reduced. Even silvering started to lose its dominance as the accepted chapter ring finish and good quality entirely brass coloured clock faces were common Towards the 19th century.

So, the main feature to look for on any clock you are likely to find at a local auction are the one handed face markings along side our traditional two handed format. The enigma of reading two hands at once was to0 much for the the average Baldrick between 1700 and 1730 or so. After that they got it and the markings dissapear from clocks made thereon. This strongly indicates a clock made in the period you are looking for i.e. early 18th century.

The key decorative features are the graduations on the inner of the chapter ring and the fleur-de-lys although you must have both to be confident your looking at something pre-1730. The fluer-de-lys is one feature that persists even today on modern clock dials and I do wonder sometimes if the people who put them there really know why they are doing it (they are half quarter hour markers).

The inner chapter ring markings I am referring to are the ones that look like the mirror of the minute markers on the outer chapter ring, but if you count them you will find there are 4 and not 5 “minutes”. This is because they are not minute markers, they are quarter hour markers meaning that you can just look at the hour hand to read the time without needing to even understand what the minute hand is for. Literacy levels were low in 1700 and up until then clocks only had one hand to keep it simple.

There is one other thing. If the maker at the bottom is Fecit Londini or some thing similar, this is not the maker. Its Latin for “created in London” and only appears on rare old clocks. If you find a clock with this written on it and its going cheap I have some instructions for you….

- Get “Braintree Clock Repairs” written on the receipt.

- Phone me we can arrange to meet me in a remote location on a dark night with no witnesses. Dont tell anyone where you are going.

Everything will be fine and you will be heard of again. Oh and bring the receipt and the clock with you. For evaluation. I will bring a shovel…… for evaluation purposes.

Assuming you haven’t found a Tompion and are just about to phone me you will probably need to consider the case of the clock now you have roughtly dated the face. The first thing to establish is if the case original to the clock.

To check out the case and see if it is original to the clock take off the head by pulling it forward. Ask a porter at the auction house to do this – they will be more than happy to do so. It slides forward like a drawer and has no rear if you just want to have a quick peek with out asking. Having said this I’ve taken many a grandfather clock head in the head as they tend to be a bit wobbly. Also be aware that the door swings open on the front so if you don’t want to be wearing the clock glass frame like a medieval torture instrument then maybe get some help from the auction porters!.

At any rate, there should be no modification to the original movement mounting plank and support. This is really important so pay attention to the next few paragraphs as this is where you might score or lose on your purchase.

The clock was put together by a cabinet maker, not a bodger, so if there is any bad joinery or bits that just look like theyve been cut to fit badly its almost certainly a “close but not quite ideal” transplant from another clock case. Thats fine and not a problem but dont pay for a match when your buying a marriage!. Very true. Im not bitter. Twice.

So look closely, it should look perfect and be joined to the rest of the case consistent with original production. Supports from the main body should run from this section though the main structural body of the clock and LOOK like they are well thought out and originally installed. The joinery methods should be consistent. Look carefully at the base plank on which the movement sits. Is it the same age and colour as the supports? Is the width right? Does the face line up parallel with the body of the clock?.

If these things are not right then the case is more than likely new to the clock.

Think about it…if you had to make a plank to sit on two strutts and it was the finishing job of something that cost the same as a car… would you mess it up and leave it looky scrappy?. No. You would get it exactly right.

Thats what you are looking for. Think like the person who built it. He trained in a guild by candlelight and got stabbed with quill pens in the back of the head by his boss if he got it wrong. Is what you are looking at, the product of that level of motivation?. Its not complicated to work out in most cases.

Swaping old heads into younger cases has been common practice for years and case design is generally so conservative that stylistically its actually hard to find a head that wont match a case from an aesthetic perspective providing its the right size. They frequently ARE the right size because the sizing of the heads was controlled by the guilds. The whole movement and face assemblies therefor lent and lend themselves to subsequent transplanting. It really is like all the bottle tops mixed up on the bottles out there in marketplace.

What I am saying is that if you do get an original match you will certainly be paying a large premium for it so be certain that you are getting what you pay for.

In all honesty the best idea, and what I have done, is to buy what you like the look of and pay for a marriage not a match. Its better value and your less likely to buy badly.

My Geaorgian brass face is in a Victorian case that was chosen to fit its alcove location. I like the case and I like the clock and I consider them two different good things.

I want a Tompion in walnut but so what.

The point is I suppose that everyone makes a great fuss about “marriages” of clock and case and really, is so common now that its the norm.

Clocks older than 1730

The number one indicator for an early clock is face size. They started at 8″ or so in 1659 and then went up and inch a decade until 12″ became the standard London dial face size forever pretty much in 1700. So thats and inch a decade starting at 8″ in 1660 and evening out to the standard 12″ in 1700.

13” and 14″ clocks tend to be enamel white faces and later on – say 1780 to 1860. The enamelling process came in around the middle of the last half of the 18th century so if your is a white face then is later than 1770. In my experience 1 out of 3 or 4 clocks is a brass face with 1 in 20 being 1730 or earlier.

What’s the top of the Market in Grandfather clocks?

Well, all the kudos clocks are early (1680-1720…..) brass face from a clock snobbery point of view – the high end Tompions and suchlike can be worth millions. The white faces never get into that league although a £20k clock is not out of the question by any means – its just never a stellar value.

I do all blog work on the fly for the most part so I try and be as accurate as I can but its all from memory so.. take it at face value on that basis.

Good luck and well done on getting to the end of this epic article. I really stuck a lot of time and thought into this and had to write it over two evenings as I got more and more into it and thought of all the really important basics I could give you.

So get out there and have some fun looking at clocks and going to auctions. You will see some interesting things, learn some history (or at keast put what you know into context), and in all probability you will end up going to auctions instead of antiques centres from that point onwards.

A client (Martine – Hi Martine!) recently got a “not working” white face at auction from about 1780. She bought it on a gamble and then called me in to fix it. We got the thing running and after a bit of a face restoration and some mechanical work and a service the end bill came in at £1200 for the whole thing. Its a fantastically good price when you consider it but it was a huge risk on her part. The point is if the thing had been any more worn than it was, it could well have been much more for repairs and made the whole thing and economic farce. Dont trust your luck – BUY A WORKING CLOCK!.

Credited to: https://braintreeclockrepairs.co.uk/